Archaeological sites are theatres of another time – Minoan Kato Zakros

Exploring the silence of stones

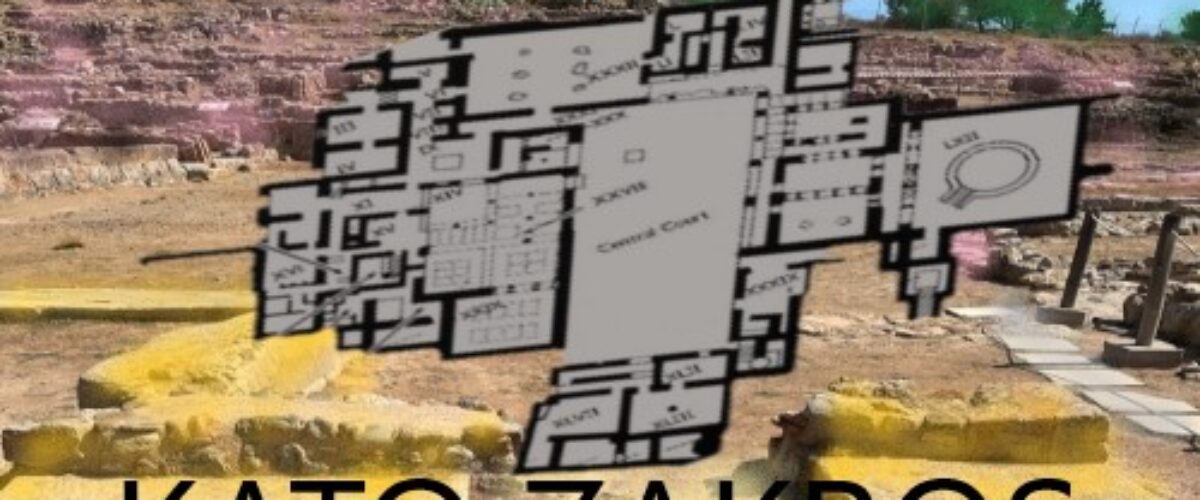

Almost at the far edge of eastern Crete, in a barren, mostly unspoilt landscape, you’ll find the Minoan Palace of Kato Zakros close to the shores of the Libyan Sea. The Minoan palace of Kato Zakros fascinates once you start imagining its past. Its existence is an act open to possibilities. The palace had about 300 rooms arranged around a central courtyard and covered an area of about 8,000 square meters. It is the fourth largest Minoan palace complex on Crete. Exploring the site you are bound to pick something up from its silent stones.

Historical footprint

The palace of Kato Zakros may not be as imposing or widespread as the more well-known palaces of Phaistos or Knossos, but its historical footprint is revelatory. From its establishment around 1900 BC until 1450 B.C. the palace of Kato Zakros was the religious, administrative, and economic centre of eastern Crete. Evidence of trade with the East were found in a storeroom in the West Wing consisting of four elephant tusks and six bronze talents. Since the Zakros Palace operated as a commercial outlet from and to the East, the palace also had access to a port through its main gate at the northeastern side.

An often overlooked trade exchange with the East was cultural. Sovereigns from Canaan and Egypt for example would hire Minoan artists to paint stylish Minoan frescoes on their palace walls. Excavations at the site of Tell el-Dabʿ in the Nile Delta region of Egypt revealed high-quality wall paintings executed in Minoan technique and style. In these palaces, dating back to the Thuthmoside period, the walls were covered with Minoan court emblems and motifs, such as bull-leaping and wrestling scenes, such as seen mainly in Knossos.

Zakros and Knossos

One of the historical enigmas of Zakros is its status in relationship to Knossos. At the time Eastern Crete was an area of strategic importance and kept an extensive trade network with the Near and Middle East. One theory assumes that Zakros, because it lacked sufficient agricultural land to sell or exchange produce, made its living from importing luxury items for Knossos. There is likewise the presumed theory that Zakros was one of the major naval bases of the Minoan fleet in Crete. And what does this say about the political structure of Minoan Crete? Was Zakros governed independently or as part of an autonomous region controlled by the monarch of Knossos?

A considerable number of Minoan buildings and clay imprints

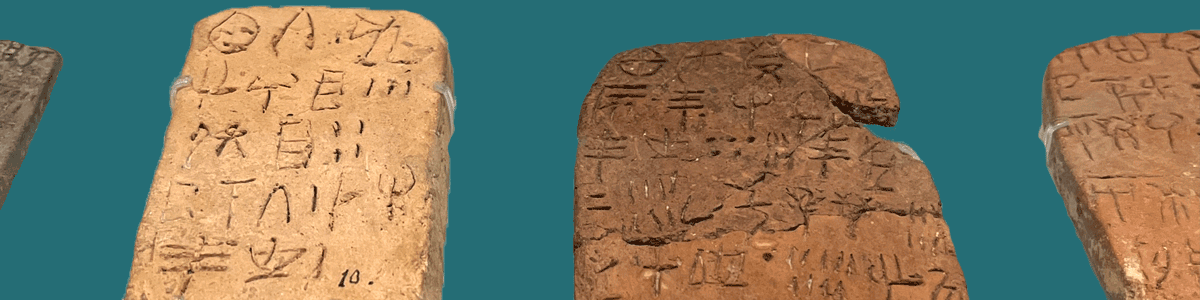

Kato Zakros was first excavated in 1901 by the British archaeologist and scholar D. Hogarth. The remains of a Minoan settlement came to the surface, indicating a flourishing and sophisticated civilisation. Hogarth found around 300 clay stamps. These clay imprints indicated an administrative system for the stock counting of (commercial) products. Some of these clay stamps dating back to 15th century B.C. originate from Knossos, another sign of a possible close relationship between Knossos and Zakros. When a typhoon hit the area in the summer of 1901 Hogarth was forced to abandon the excavation. He almost drowned, but managed to escaped by miracle.

Spectacular craftmanship

Sixty years later, in October 1961, the Ephore of Cretan Antiquities N. Platon started a new excavation in the valley of Kato Zakros. The Greek archeologist was convinced that Kato Zakros was much more than a harbour or a naval settlement. The 1960s excavations discovered a large palace complex with many typical Minoan architectural features. These include a large central court (30x12m), secondary courts, porticos, a monumental stepped entrance, one and two storey buildings, and storage rooms. Some rooms were embellished with frescos similar to those at Knossos, depicting bulls, spirals and double axes.

Contrary to palaces of Knossos, Malia and Phaistos, the palace of Zakros was not looted. During millennia it was covered by earth and left untouched. The remote location surely helped. Artefacts of great aesthetic and artistic value were found, ceremonial pots and vessels, including the most beautiful stone vessel of the Cretan-Mycenaean era. One of the highlights as well is the small (16 cm) rhyton carved in rock crystal. A real masterpiece of craftsmanship and technical skill exhibited in the Heraklion Archaeological museum. The body is made of a single core of hard stone. The neck is attached to the body by a ring of crystal beads and gilded ivory discs. Nobody knows which techniques were used to carve it or how they made the handle of spherical crystal beads threaded onto a bronze wire. To work the crystal you need a material that is harder than the crystal itself.

The architecture of the palace of Kato Zakros

The architecture of the palaces of Knossos, Phaistos, Malia and Zakros in the first period around 2000-1900 B.C. seems to be based on an organic building structure. The natural environment, mostly the climatic and geological conditions, dictated the construction more than geometric principles.

The palace was not only the king’s residence, but also the centre of religious, economic and political life. Living quarters, reception halls, sanctuaries, warehouses and workshops are all grouped around a central courtyard. Columns are a fundamental element of Minoan architecture. The living quarters are often located on the east side, sometimes spread over several floors, connected by stairs. On the west side are the warehouses and the religious spaces. From the terraces with overhanging gardens, colonnades and loggias, one looks out over the landscape.

Similar to many other Minoan buildings on Crete, the Zakros palace and the town were suddenly destroyed around 1450 BC, marking the end of the Neopalatial period.