Exciting ancient Minoan finds in the waters near Crete

A woman, the Cretan sea and a Minoan shipwreck

There is a land called Crete in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair, rich land, begirt with water, and therein are many men, past counting, and ninety cities.

*Homer, Odyssey

Elphida Hadjidaki, a Greek sea archaeologist

Ancient Crete has intrigued and seduced archaeologists for a long time. For sea archaeologist Elphida Hadjidaki-Marder this seduction started early. Growing up in Chania, Crete certainly helped. Jumping in and out of the sea from a young age too. Combine this with being an avid reader of books on ancient Greece, and it is clear how Elphida developed her passion for sea archaeology that became to define her life. Her interest in ancient harbours and her many dives allowed Elphida Hadjidaki to make significant contributions to the field of underwater archaeology. One of the highlights of her archaeological career was finding the first-ever Minoan shipwreck near the coast of Crete. “I always wanted to find a Minoan shipwreck,” she said in interviews, “so I started looking for one near the island of Pseira.”

Crete is known as the island of the Minoans

It was the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans who came up with the name Minoans, and not the Minoans themselves. Evans named the Minoan civilization after the legendary king Minos. However, their origin probably lies elsewhere. DNA analysis of Minoan skeletons indicates that these Minoans are probably descendants of a people that reached Crete about 9000 years ago as part of a migration wave from Anatolia. The Minoan era, this sophisticated ancient Bronze Age civilization, lasted approximately from 3100 B.C. to 1050 B.C.

The Minoans, the legendary people of the sea

The earliest ruler known to have possessed a fleet was King Minos. He made himself master of the Greek waters and subjugated the Cyclades. Minoan seafaring opened up trade routes with other parts of the Mediterranean basin. There are plenty enough images of ships on frescoes, but a Minoan shipwreck was never found. Until sea archaeologist Elphida Hadjidaki and her team received funding from the Aegean Prehistory Institute in 2003 to dive for Minoan shipwrecks near Crete.

Following your instincts pays off

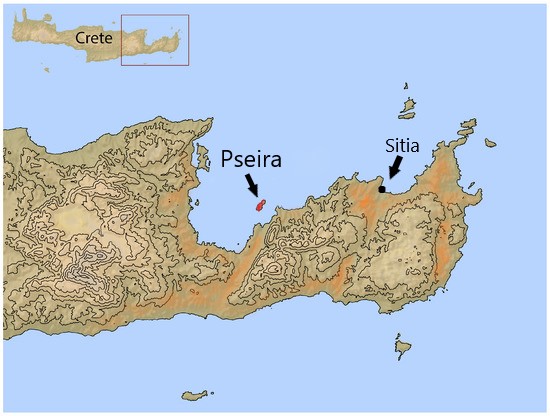

After receiving the grant Elphida and her team started sonar scanning the seabeds. They detected 20 possible sites, however, these sites did not provide anything interesting to research further. In the last days of the 2003 sea survey, Hadjidaki decided to follow her instincts and take her team to the area around the small island of Pseira on the northeastern coast of Crete, opposite Mochlos. She knew that the area was first researched by the famous sea explorer Jacques Cousteau in 1975-1976. At the time Cousteau was looking for signs of the lost continent of Atlantis within a certain diameter of the island of Santorini. Instead, Cousteau found Minoan pottery in the waters near Pseira. At the time Cousteau assumed the pottery to come from sunken ships in the harbour of Pseira, the result of a volcanic eruption around 1500 B.C. Nowadays the pottery is believed to come from the collapsed harbour houses on Pseira. Elphida Hadjiki and her team resolved not to go to the spot where Cousteau dived, but just off it and dive deeper. Actually they did not have to dive deep, soon on the sea floor they found an area lined up with amphoras, cups and jugs.

Pseira island Crete and some underwater pottery found there

Pottery from the Middle Minoan period around 1800-1700 B.C.

In 2004 she returned with a bigger team to map the site. The year 2005 saw the start of a large-scale excavation. Unfortunately, no wood from the ship survived. The assumption is that the ship capsized with the cargo down and the hull on top. That is also the most likely scenario to explain why no wood has been preserved underwater. As they excavated further they found some objects identifiable as amphoras and jars probably used for the transportation of wine or olive oil, but also cups and the fishing gear of the ships’ crew. When Philip Betancourt, a Minoan pottery expert, examined the ceramics he was convinced that the pottery all originated from the East of Crete. And, that the pieces of pottery came from the same period, the so-called Middle Minoan period around 1800-1700 B.C. In total Hadjidaki’s team brought to the surface some 209 ceramic vessels, of which 80 are nearly whole.

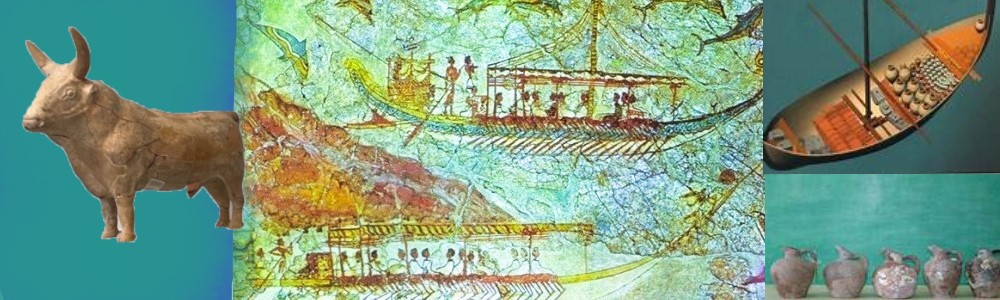

Collage of Minoan fresco, example Minoan ship and pottery

Coast-hopping Minoan seafarers

Based on what has been found, the ruminants of the wreck seem to indicate that the shipwreck has been busy with coast-hopping journeys. Imagine a small coastal vessel making stops along the coast of Crete. It also indicates that for local traders sea trade was much easier than crossing the mountains from north to south or east to west.

Hadjidaki and her team completed the excavations at the end of September 2009 feeling accomplished to have found the first and only Minoan shipwreck to date. Moreover, it contained the largest complete clay vessel cargo ever excavated from the Middle Minoan IIB period. And even more valuable, it provides information about the seafaring Minoan people and their success as traders.

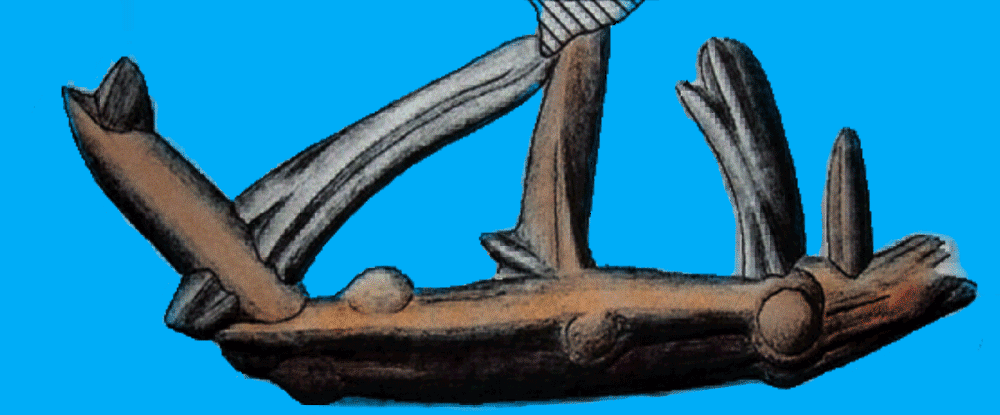

clay seal Minoan ship found on Pseira

A marvellous glimpse into a time when the Minoans first started building their palaces

It really gives a glimpse into a time when the Minoans first started building their palaces. The shipwreck’s cargo not only indicates local trade on the eastern Mediterranean shores, it also validates other archaeological findings. Trade was done by sea. Minoan ships were capable of importing many of the raw materials required to fuel the development of one of Europe’s first great civilizations. This was all done by sea.

How the ships looked we don’t know exactly although there are frescoes and some old stone seals that depict images of different types of ships. The Minoans traded throughout the Mediterranean. The Minoans were good seamen, seafaring was in their blood. The Minoans maintained trade routes with Egypt, Syria, and the Greek mainland. The routes may even have extended as far west as Italy and Sicily. The world really should thank Elpida Hadjidaki-Marder for having the instinct and knowledge to look for the Pseira ship. Finding and excavating the first example of a Minoan vessel shed light on a hidden world that could change our perceptions of the capabilities and sophistication of ancient Greek civilizations.